Frequenting the historic Cathedral Hill neighborhood in St Paul always makes me feel that I am walking in the footsteps of F. Scott Fitzgerald.

St. Paul’s historic Cathedral Hill is one of my most favorite neighborhoods in the Twin Cities. Because I’ve always lived on the Minneapolis side, it seems like a visit to another world, even though it’s a just a short drive across the Mississippi River.

Frequenting Cathedral Hill’s side streets and shops, and tarrying in the restaurants and watering holes located in its vintage buildings always makes me feel that I am walking in the footsteps of F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Table of Contents

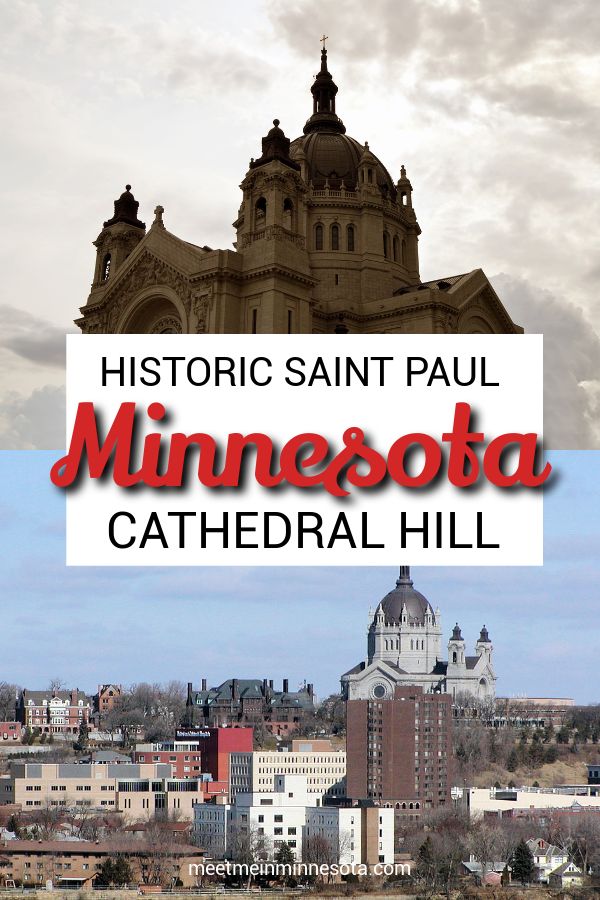

The Saint Paul Cathedral

Cathedral Hill is situated on a bluff overlooking downtown St. Paul, dominated by the majestic dome and imposing edifice of the National Shrine of the Apostle Paul. Archbishop John Ireland (don’t you love that name?) commissioned French Beaux Arts architect Emmanuel Louis Masqueray (who’d worked on the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair) to build a centerpiece for the Archdiocese. Construction began in 1906 and was completed in 1915. It was during this time that the neighborhood began to flourish, although it had been a place of elegance and grandeur from the mid-19th century on.

When my brother visited Minnesota, we decided upon a whim to go inside the Cathedral, and were fortunate to tag along on a tour already in progress. Spellbinding details were woven into historical, religious and humorous context by the tour guide, an elderly woman who clearly was in love with her work.

The Cathedral’s French Renaissance interior is filled with gilt, marble statuary, stained glass windows, intricate carvings and glorified not only by ornament but its immense, yet intimate, proportions. It is impossible to depict how large this building is with photographs, but its detail will remind you of the places, like the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris, which inspired its designers and artisans.

Legend has it that one of the city’s most prominent citizens, James J. Hill, was unhappy that the Cathedral next door eventually overshadowed the grandeur of his personal residence not only in expense, but proximity to heaven. Closer to God is the mighty dome of the Archbishop instead of the railroad baron. Perhaps as it should be, no? In the photograph you can see the multi-chimneyed abode of Mr. Hill made modest.

The Haunts of St. Paul’s Literary Son: F. Scott Fitzgerald

Cathedral Hill began to be developed in the 1850s. It is also known as Summit Hill, after Summit Avenue on which wealthy citizens built residential monuments to themselves. These addresses literally looked down on St. Paul’s crass commercial district and their less fortunate neighbors in the flats leading to the river’s edge. But Cathedral Hill’s glory days may very well have occurred during the Jazz Age of the 1920’s and 30’s.

One of St. Paul’s favorite literary sons, F. Scott Fitzgerald, immortalized this insular world in his stories and novels. Who couldn’t love The Great Gatsby from its first few pages, evocative as it is of something close to deja vu in sepia tones of forced gaiety and underlying melancholy? Just like the lace-curtained windows on Laurel or Ashland that provide only glimpses of the lives contained within, nostalgia renders Cathedral Hill’s literary portrait. “That’s my Middle West,” Nick Carraway tells us. “. . . the street lamps and sleigh bells in the frosty dark and the shadows of holly wreaths thrown by lighted windows on the snow.”

Early in our relationship, my ex-husband and I spent a romantic evening at a table for two next to the fireplace at W. A. Frost and Company, at the corner of Selby and Western in Cathedral Hill. We’d stumbled and slid through snowbanks into a bar that seemed bathed in Carraway’s golden light, and proceeded into a dining room made intimate and mellowed by woodgrain, oriental carpets, and vintage brick.

Note: For other places in this neighborhood to have a romantic evening, check out Romantic Things to Do in Minnesota.

As a boy, F. Scott, named after distant cousin Francis Scott Key before his poetry became famous as our national anthem, was sure to have had an ice cream soda here when it was the neighborhood drugstore. The building is a handsome sandstone edifice in the Italian Renaissance style, ornamented with copper cornices. Its original tin ceilings gleam in candleglow.

Across the street to its west is the former Angus Hotel, dating from 1887, now refurbished as the Blair Arcade with shops and condominiums, including Garrison Keillor’s bookstore for a time. Scott’s mother, Molly, lived here after her husband’s death. The bay windows and turrets on the building are classic Queen Anne with wrought iron ornamentation. The Angus alternately deteriorated and rejuvenated in 20-year increments after WWII, and now is at the nexus of the neighborhood.

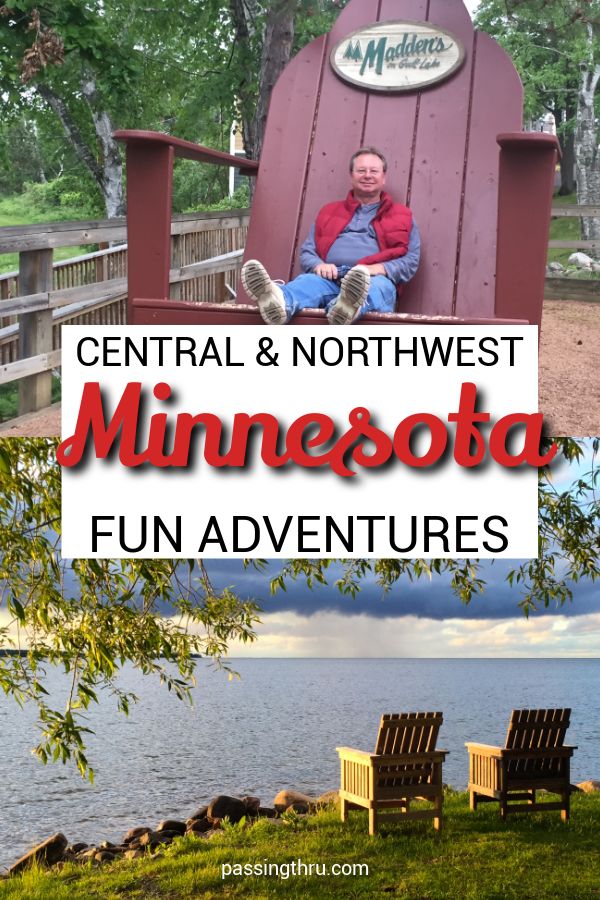

On this visit, my girlfriends and I headed to Cathedral Hill to shop at First Monday at The Commodore Hotel, which had been a temporary home to Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald in the fall and winter of 1921-22. Another of our friends was displaying her handmade jewelry at this shopping event and we were all excited to be there. While it might be cliche to suggest walking through the Commodore’s double doors was like stepping back in the footsteps of F. Scott Fitzgerald, it wasn’t a stretch to imagine a white-gloved doorman standing ready under the broad-striped canopy at our approach.

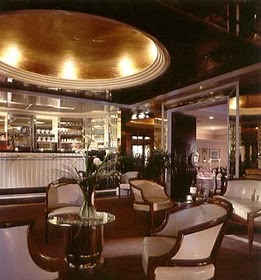

The Commodore’s Art Deco bar (note: restored, refurbished and reopened in late 2015) is a perfectly preserved example of the clean lines, mirrors and gilding with which the style purveyed swank and sophistication, and still harbors the speakeasy’s secret door to a hidden crawlspace where the booze was stashed. To replenish the bar these days, the bartenders go on hands and knees into the same closet, deftly passing bottles back toward the waiting hands of their accomplices. I ordered a cosmopolitan martini and wished I could have a cigarette, although I haven’t smoked in years.

The Commodore’s details set the mood back to the Roaring 20s and 30s in an instant. Little had they changed in the intervening decades, as evidenced by vintage photos. Tile, mirror, lighting fixtures, and even the whimsical painting on the ladies room door harkened toward that time, which has always seemed so familiar.

What is it, I am wondering in this month of ghosts, about those who frequented these places? They seem so vivid to me. Not individually do they manifest, but instead they inhabit an overall mood woven from threads of expectation, glamor, hope, and tragedy. Was life more intense then? It sometimes seems to me so. Have I lived a past life during this time? Perhaps.

The newly wed Fitzgeralds embarked on an opulent lifestyle from which Scott drew many of the plot lines in his literature, creating financial difficulties that would plague him throughout his life. After being asked to leave the Commodore and getting kicked out of the University and White Bear Yacht Clubs for wild parties, they relocated to Paris and the French Riviera, where they became friendly with other ex-pats, including Ernest Hemingway. This extravagant and worldly way of living accommodated Fitzgerald’s alcoholism and his wife’s flamboyance.

Gangsters and Hoodlums

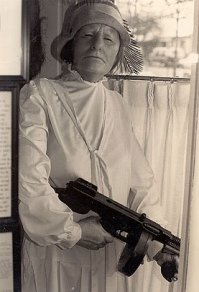

The vestiges of The Lost Generation lived on at The Commodore long after the Fitzgeralds did, mutating into the gangster days of the late 1920’s and throughout the 1930’s. In John Dillinger Slept Here, we learn that Ma Barker occupied Apartments 215 to 221 starting in 1933, using an alias. Her son, Fred, moved in, too, and brought his girlfriend, but, according to a 1936 FBI report, on mother’s orders the girl was ensconced in Apartment 404. Nonetheless, the FBI went on, Ma Barker made the girl’s life “miserable.”

Other scofflaws besides the garden variety Jazz Babies and small-time hoodlums who holed up at the Commodore were Alvin Karpis, Al Capone, and train robber Jimmy Keating. Karpis hooked up with the Barker gang about this time to kidnap William Hamm, one of the scions of the St. Paul brewing dynasty, netting the princely sum of $100,000 in ransom. Next, they doubled their money with Edward Bremer, of the banking family, whose father was a friend of Franklin D. Roosevelt. Residents of the Commodore lived fast and furious. Things were all over for the Barker gang by 1935, with everyone either dead or captured. The Commodore declined, particularly after the second World War, along with the neighborhood.

Social Climbing and Ideals

This was all long after young Scott came of age in the shadow of the construction of the magnificent Cathedral. The cohesiveness of the neighborhood must have impressed the boy as representing haven and strength. Edward Fitzgerald was fortunate to have “married up” into local McQuillan wealth and Social Register standing. Whenever he fell upon hard times, and he frequently and inevitably did, the family returned to the financial safety of one of his mother-in-law’s houses in Cathedral Hill.

The sense of stability and place permeating Fitzgerald’s work, according to Patricia Kane, in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s St. Paul: A Writer’s Use of Material, was more symbolic than actual. Fitzgerald’s family “lived always in houses on the periphery of the city’s ‘best’ residential district. Fitzgerald’s letter to a friend described himself as living:

‘In a house below the average

On a street above the average

In a room below the roof. . .’ “

while at 599 Summit Avenue, now listed on the National Register, and working on This Side of Paradise. It was here that he learned of his book’s acceptance for publication, which in turn prompted a renewed liaison with Zelda and led her to consent to marriage now that he was appropriately successful.

All Fitzgerald’s stories, Kane tells us, include men “whose expectations exceed their experiences.” Another Minnesota writer, Sinclair Lewis, who also resided for a time at the Commodore, similarly immortalized in the character of Babbitt an “admiration for the energy of the city and the Ivy League athletes come home to business success.” Fitzgerald wrote of an ideal city, whose values and experiences were predictable and sturdy.

The irony of this repetitive theme isn’t lost on someone who traces Fitzgerald’s transient life, his parents having lived at six addresses on and off Summit Avenue between 1908 and 1918 alone. The newly wed Fitzgeralds lived at the Commodore in the fall of 1921, but also during that short period of less than a year, he and Zelda moved frequently between White Bear Lake and Cathedral Hill, most frequently as a result of eviction for the effects of wild parties they hosted. By 1922, they were gone from Minnesota for good.

Walking Tour of Cathedral Hill

It was a beautiful Midwest autumn evening to walk through the neighborhood from the Commodore to W. A. Frost, where we friends were anticipating good food and wine. We decided to meander a bit in the footsteps of F. Scott Fitzgerald to take in parts of the Walking Tour on our way. Ambling west on Laurel, we admired beautiful examples of mid to late 19th-century architecture as the leaves fluttered from the trees and the streetlights came on. It wasn’t hard to imagine a young boy skipping down the street and glancing up at the different homes up and down the block, taking in the atmosphere in indelible imprints to be resurrected later in his writing.

Did he admire the detailed simplicity of this one or that one, or perhaps know the family who lived over there? Would he and his playmates have scampered in the garden behind the hedge or opened the turquoise door on the spindled porch to beg a sweet treat from someone’s mother?

At # 481 Laurel, one of a twin set called San Mateo Flats by its builder, Scott had been born in 1896, in the third-floor apartment at left. On this waning fall afternoon with the sunset filtered by buildings and trees, the golden lamplight such as Nick Carraway described in The Great Gatsby was glowing in the front flat like a beacon for a boy on his way home to dinner.

We turned on Mackubin northward toward Selby, and then east again. The streetlamps were lit, and the dome of the Cathedral rose up at the end of the street, the ever-present landmark that the boy saw on his way for an ice cream all those years ago.

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

We friends dined that lovely evening among the shadows of what had gone before. We spoke of our own hopes and dreams, laughed and confided in one another, all in the space of a few golden hours. Amid the quiet streets, we saw the romance and heard whispers of the past as the city settled in. The days are shorter now and we will return again.

Check out places to stay in and near the Cathedral Hill neighborhood, and use our handy interactive map to book directly: